On skin color, Xiang says the efforts to develop additional and improved measures will be unending. “We need to keep on trying to make progress,” she says. Monk says different measures could prove useful depending on the situation. “I’m very glad that there’s growing interest in this area after a long period of neglect,” he says. Google spokesperson Brian Gabriel says the company welcomes the new research and is reviewing it.

A person’s skin color comes from the interplay of light with proteins, blood cells, and pigments such as melanin. The standard way to test algorithms for bias caused by skin color has been to check how they perform on different skin tones, along a scale of six options running from lightest to darkest known as the Fitzpatrick scale. It was originally developed by a dermatologist to estimate the response of skin to UV light. Last year, AI researchers across tech applauded Google’s introduction of the Monk scale, calling it more inclusive.

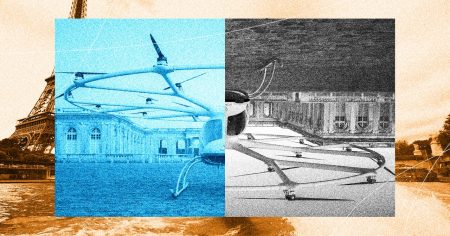

Sony’s researchers say in a study being presented at the International Conference on Computer Vision in Paris this week that an international color standard known as CIELAB used in photo editing and manufacturing points to an even more faithful way to represent the broad spectrum of skin. When they applied the CIELAB standard to analyze photos of different people, they found that their skin varied not just in tone—the depth of color—but also hue, or the gradation of it.

Skin color scales that don’t properly capture the red and yellow hues in human skin appear to have helped some bias remain undetected in image algorithms. When the Sony researchers tested open-source AI systems, including an image-cropper developed by Twitter and a pair of image- generating algorithms, they found a favor for redder skin, meaning a vast number of people whose skin has more of a yellow hue are underrepresented in the final images the algorithms outputted. That could potentially put various populations—including from East Asia, South Asia, Latin America, and the Middle East—at a disadvantage.

Sony’s researchers proposed a new way to represent skin color to capture that previously ignored diversity. Their system describes the skin color in an image using two coordinates, instead of a single number. It specifies both a place along a scale of light to dark and on a continuum of yellowness to redness, or what the cosmetics industry sometimes calls warm to cool undertones.

The new method works by isolating all the pixels in an image that show skin, converting the RGB color values of each pixel to CIELAB codes, and calculating an average hue and tone across clusters of skin pixels. An example in the study shows apparent headshots of former US football star Terrell Owens and late actress Eva Gabor sharing a skin tone but separated by hue, with the image of Owens more red and that of Gabor more yellow.

When the Sony team applied their approach to data and AI systems available online, they found significant issues. CelebAMask-HQ, a popular data set of celebrity faces used for training facial recognition and other computer vision programs had 82 percent of its images skewing toward red skin hues, and another data set FFHQ, which was developed by Nvidia, leaned 66 percent toward the red side, researchers found. Two generative AI models trained on FFHQ reproduced the bias: About four out of every five images that each of them generated were skewed toward red hues.

It didn’t end there. AI programs ArcFace, FaceNet, and Dlib performed better on redder skin when asked to identify whether two portraits correspond to the same person, according to the Sony study. Davis King, the developer who created Dlib, says he’s not surprised by the skew because the model is trained mostly on US celebrity pictures.

Cloud AI tools from Microsoft Azure and Amazon Web Services to detect smiles also worked better on redder hues. Nvidia declined to comment, and Microsoft and Amazon did not respond to requests for comment.

Read the full article here