Just over one year ago, I published on Seeking Alpha an article about Heritage Global (NASDAQ:HGBL) wherein I expressed concerns about their rapidly expanding line of business, a “specialty lending” unit that provides financing to buyers of charged-off loan portfolios. I considered the venture to be outside their wheelhouse and I enumerated various points detailing the complexities of charged-off loans being sold in a secondary market and its impact on collectability. Given my research, I was therefore unsurprised when management recently announced a problem with their largest borrower in this segment. Required minimum payments were not being made, and the loan is in default status. My intent with today’s article is to review in brief the problems I had anticipated in that earlier article, how they are manifesting themselves now, and what the impact on HGBL will be moving forward. Bottom line up front: Heritage Global took on too much risk in a segment they don’t yet have sufficient expertise in. They are at high risk of losing principal on the loan, but haven’t sufficiently accounted for that risk. The segment isn’t performing even close to what they anticipated gaining out of it, and that was true even before this troubled loan scenario. The whole situation challenges the narrative of the company being “counter-cyclical” or a hedge against a recession. Avoid HGBL.

The Trouble With Troubled Debt Markets

The problem with getting into the bad debt market is several-fold (I cover all these points in WAY more detail in the other article, but summarized here):

1) Transparency is lacking as it relates to the documentation and detail that buyers of charged-off loans receive about each loan when they buy a package of them. This unfortunate matter exists logically. When loans go into default, it is often accompanied by a cessation of communication between the creditor and the debtor. If something mortal happens to the debtor, there is no one to communicate with. If the debtor finds themselves unable or unwilling to pay back the loan, it is common for them to ghost the creditor in hopes of escaping the required payment. Compounding this with the fact that these loans are packaged together by the thousands, even starting a collection effort is challenging.

2) Recoverability rates for charged-off loans are predictably low, 12% at the median and 17% at the average. Naturally, buyers of debt always demand and always get these loans for pennies on the dollar, to the tune of 4.5 cents per dollar of original value. That way, even if they only recover a fraction of the loans, they can still make a profit. But the point remains that there is great risk here, particularly because not all collection agencies are created equal. It would be helpful to know the vetting process HGBL underwent for each entity they are making loans to.

3) Of utmost importance is the amount of time on average that a loan book has been in default. The longer the default has lasted, the harder it is to make a recovery. Success rates plummet after just a few months. Unfortunately, HGBL doesn’t publish any data related to the average age of the defaulted loans package that their borrowers bought.

On top of these issues that pertain to bad debt markets generally, how HGBL entered the space particularly is of concern. It seems to be a classic case of too much too fast, with these investments in bad debts going from $2 million to $35 million in just two years! On top of that, HGBL chose to expose themselves to significant concentration risk, with a single debtor making up 66% of their total investments. Per the 10Q:

As of June 30, 2024, the Company held a gross balance of investments in notes receivable of $35.2 million…. and consisting of one borrower’s note balance of approximately $23.1 million, or 66% as of June 30, 2024.

Lo and behold, it is that debtor who is now struggling to collect.

Default

We don’t know much about this now bad loan that was used to buy bad loans. The first sign of trouble arose sometime in the 3rd quarter of 2023. CEO Ross Dove opened the conference call for that quarter by saying:

So our largest borrower came to us and said that they would like to extend the term of their loan that they believe they’ll definitely be able to pay off. However, the collection curves have slowed, and they’ve asked for an extension. So we feel comfortable that it’s going to work, but we took the $900,000 charge because the buyer is asking for an extension.

So over time, we’ll have to figure out whether or not that charge or that noncash reserve will stay on the books. For now, we believe it was prudent and the safest thing to do.

The language of the 10Q was as follows:

Currently, declining collections are being experienced industry-wide and are expected to continue in the short-term. While most of the Company’s borrowers are still tracking to their collection forecasts, the Company’s largest borrower has requested extended repayment terms due to declining collections. The Company is working with the borrower and its partners to finalize amended loan agreements. An amended loan agreement would allow the borrower to meet their minimum required payments over a longer repayment period with a higher interest rate. In the event that the borrower defaults on a loan, the Company expects to recoup the majority of principal and interest owed, albeit over a longer period and with more uncertainty than an amended loan agreement. Due to the inherent risks and uncertainty of this situation, the Company has increased its reserve for credit losses by $0.9 million to $1.4 million.

Subsequently, both the 10K and annual conference call briefly mentioned what happened in Q3, but with no new updates. In the conference call from Q1, they said nothing about the loan. Then we get the Q2 report and suddenly the loan is in default. Peculiarly, this time around, the CEO didn’t address the elephant in the room at all in his prepared remarks. It was buried in the middle of the prepared remarks by CFO Brian Cobb, after talking about several other matters:

…. the company’s largest borrower has had continued difficulties meeting their obligations. This borrower continues to collect on the underlying portfolios and remit these collections to the company net of servicing fees. However, these net collections are currently not sufficient to satisfy all minimum required payments. Beginning in June 2024, after this borrower’s June remittance fell short of the minimum amount due, the company placed the loans on nonaccrual status. The company’s share of payments received on loans and nonaccrual status, including interest, will be applied against the outstanding balance.

The default is currently expected to reduce the company’s total 2024 operating income by approximately $1.6 million. It is important to reiterate that Heritage Global is a profitable, diversified business with multiple growth avenues going forward.

The operating income they will now miss out on will reduce expected EPS by $0.04, in a year where they are already behind 2023 by $0.03.

Naturally, analysts during the Q&A session wanted more information about the bad loan. There we learned that, after the initial charge of $900,000 mentioned above when the loan was restructured back in Q3 2023, the allowance for credit loss was not increased in spite of the loan further deteriorating here in Q2 2024! This to me is peculiar. When the borrower first faced some trouble, the loan terms were amended to make it easier for obligations to be met. This incurred the initial loan loss reserve increase due to the signs of stress. But now, when the borrower isn’t even able to abide by the more relaxed terms, management doesn’t think that warrants a higher loan loss reserve?

But it gets weirder. On June 30, 2023, the company had a balance of $22.2 million with this one borrower. At the end of September 2023, the quarter in which the borrower asked for help, that balance had fallen ever so slightly to $21.8 million. That’s good. But then, in the year-end report, we learned that the loan balance to that borrower GREW by $2 million, up to $23.8 million. Why in the world did they loan more money to the very entity that was struggling?! Wouldn’t they want to reduce exposure to them? Perhaps I said it best in my earlier article: “I wonder if HGBL is so eager to chase this opportunity that they relaxed their standards for who they would loan to.” The entity to whom they have thrown the most money at in this space is the one who is struggling, and they gave them more money even after they started struggling. Big red flag.

Financial Impact

If we take the current loan loss reserve on their books of approximately $1.4 million strictly at face value, HGBL loses only $0.04 worth of value per share. Why therefore did the stock lose $0.60 when the news dropped, erasing 25% of the company’s market cap?

I think the market has lost trust in management as it relates to this business line. Clearly, the market doesn’t think the $1.4 million reserve is big enough. The stock has regained some of the loss and sits currently at ~$1.85. If we do the same math as above in reverse, the $0.47 drop in per share value translates into an expected loss of $17.3 million on these loans. That’s what the market is perceiving as the actual risk.

Secondly, maybe the market isn’t buying the “we are counter-cyclical” narrative that management and others have shared as it relates to HGBL. The story has long been that recessions create conditions where people need to sell off assets, and that creates ripe conditions for HGBL. As it relates specifically to this specialty lending line, everyone was talking about how recessions create an increase in charge-offs, and therefore that more entities will want loans (presumably from HGBL) to buy up packages of these defaulted products to try and collect on them. What no one mentioned, except for me, it seemed, is that while charge-offs will, of course, go up with a recession, collectability will, of necessity, go down for the very same reasons of a bad economic climate! Management themselves seemed to let the cat out of the bag in this regard in the conference call, challenging their own long-standing narrative:

…. we are in an economic environment where consumers have less capacity to pay their debts, which results in lower collection rates industry-wide.

If the economy gets worse, perhaps HGBL won’t be a counter-cyclical play after all.

Zooming Out

It’s important to take a closer look at what HGBL expects this specialty lending business line to achieve writ large. Each of their filings has this explanation:

“In general, we expect to earn an annual rate of return on our share of notes receivable outstanding in accrual status of approximately 20% or more based on established terms of the loans funded and performance of collections.

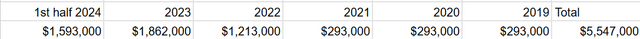

Since this business line has been in place since 2019, we can gather the data to see if this is coming true.

Total loans made since 2019 in the specialty lending segment amount to $67.3 million. They publish that updated number every filing. The money they have made off those loans was a little harder to tease out, especially since they didn’t start publishing that specific number until 2021. Prior to that, all monies made in specialty lending were looped together with their National Loan Exchange unit (that brokers loans) and together it was called “Financial Assets”. But we do know that the business line started small and has grown every year. To be generous, let’s assume that HGBL made as much in specialty lending in 2020 and 2019 as they did in 2021. The operating income would therefore look like this:

operating income chart (Company filings)

Dividing that $5.5 million by the $67.3 million is only a return of 8.2%, a far cry from the 20% target. Granted, with most of the loans made only recently, and with management’s stated time frame of the loans lasting between 2 and 4 years, we know that they haven’t got the full return on some of them yet. But even dividing by the total loans made as of the end of 2022, which was $34.3 million, by all the operating income they have made through the present, it’s STILL below the 20% they claim, coming in at 16.17%. There is a huge disconnect between what they say they will earn on these loans and what they are actually earning.

Between the troubled loan issue and the rate of return falling way short of expectations, it’s worth heaping extra scrutiny on this specialty lending segment and, of course, by implication, the entirety of the HGBL investment thesis.

Executive Compensation

I can’t write about HGBL and NOT bring this up. I go into more detail in my other article that exclusively treats this matter, but the crux is this: executives at HGBL get paid an annual bonus that is calculated as a percent of net operating income. The problem with this, of course, is that it makes operating leverage impossible. When companies add incremental income to a fixed cost base, those added monies travel straight to the bottom line. But when your cost base is NOT fixed but floats up alongside income, then the possibility for margin expansion is eliminated. What’s worse is that the bonuses for these guys don’t require a minimum level of execution, AND there is no cap. Summarized from the proxy:

– The CEO gets a floating bonus that slides between 1% and 7.5% of company-wide operating income, where he gets a higher percent if they make more.

– The head of financial assets gets a flat 12% of the net operating income of his division.

– The head of industrial assets gets a flat 10% of the net operating income of his division.

To be clear, this is a bonus on top of their salaries. In 2023, between these three executives, almost $4 million was doled out. That’s a staggering $0.10 worth of EPS in a year where they had EPS of $0.33. How many companies do you know where the pay for the top three executives alone reduced EPS by almost 25%?

In the context of the main thrust of this article, which is problems in their specialty lending segment (which falls under the financial assets division), how appropriate is it to give a 12% flat bonus to the individual who made the decision to concentrate $23 million into a single customer, which customer is now losing them money? Compensation should be more directly tied to performance in ways where the pay is at risk, not a guaranteed percent. I know of no other company where the executives shave a percent off the top, no strings attached.

Bigger picture, compared with their near-peer in RB Global (RBA) (RBA:CA), HGBL has SG&A as a percent of revenue of 43% (full year 2023) whereas RBA has it at 20%. Compensation expense alone at HGBL is 31% of revenue. In other words, HGBL pays out more in compensation alone than RBA does in all of SG&A when taken as a percent of revenue.

Risks to My Thesis

If the troubled borrower quickly gets back on track with interest payments, naturally the stock is probably going to go back up to at least where it was before the bad news broke. Not only will the $1.6 million ($0.04 worth of EPS) come back into play that they said they wouldn’t get this year, but also the loan loss reserve will reverse and put an extra $0.02 back on the bottom line. Even at the current narrow P/E ratio of 6, that $0.06 would in theory put $0.36 back on the price per share, a 19% improvement.

Investors should be aware that because we have been told so little about this troubled loan, it’s nearly a coin flip as to how it will resolve, so long as that coin is three-sided. It will either clear up quickly, and they make money on the loan, it will drag on for a while and HGBL will get their principal back but little to no return, or it will get worse and HGBL loses principal.

Conclusion

A customer in default on a huge loan. The “counter-cyclical” narrative being disrupted. A poorly structured compensation scheme. These are huge overhangs that aren’t likely to subside in the short term. It is my opinion that an investment in HGBL common stock should be avoided. The risks are too great. Frankly, management behavior is congruent with my “avoid” thesis. Executives and board members used to routinely buy batches of common stock, and they were doing so at prices as high as $3.17 back in August of last year, and the most recent purchases were in March of this year around ~$2.80. The price has since plummeted sub $2.00 and there is zero insider buying.

All told, this is a company to stay away from, at least until there are obvious and durable signs of improvement with their troubled borrower.

Editor’s Note: This article covers one or more microcap stocks. Please be aware of the risks associated with these stocks.

Read the full article here